SWAIS2C I Record-breaking sediment core provides unprecedented evidence of West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat

A New Zealand co-led international team has drilled the longest-ever sediment core from under an ice sheet, providing a record stretching back millions of years that will help climate scientists forecast the fate of the ice sheet in our warming world.

The 228 m of ancient mud and rock was drilled from under 523 m of ice. This game-changing scientific and technological achievement took place more than 700 km from the nearest Antarctic station (Scott Base), at a deep-field camp at Crary Ice Rise on the edge of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The sediment core holds an archive of past environmental conditions at the site from warmer periods in Earth’s history, vital information for climate scientists to determine how much and how fast the ice sheet will melt in the future under our warming climate.

The vast West Antarctic Ice Sheet holds enough ice to raise global sea level by 4-5 m if it melts completely. Satellite observations over recent decades show the ice sheet is losing mass at an accelerating rate, but there is uncertainty around the temperature increase that could trigger rapid loss of ice. Up until now, ice sheet modellers have relied on geological records from further afield.

The new sediment core, recovered by SWAIS2C (Sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to 2°C), a project with Earth Sciences New Zealand, Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington, and Antarctica New Zealand at the helm, provides a direct and comprehensive record of how this margin of the ice sheet has behaved during past periods of warmth.

“This record will give us critical insights about how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and Ross Ice Shelf is likely to respond to temperatures above 2°C. Initial indications are that the layers of sediment in the core span the past 23 million years, including time periods when Earth’s global average temperatures were significantly higher than 2°C above pre-industrial,” says Co-Chief Scientist Dr Huw Horgan (Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and ETH Zurich and WSL, Switzerland).

Preliminary dating of the sediment carried out in the field was based on identification of tiny fossils of marine organisms found in some of the layers. A wider team of scientists from the 10 countries collaborating in the SWAIS2C project will apply a range of techniques to refine and confirm the age of the records.

Evidence of open ocean where there is now 500-m-thick ice

As the team drilled down through the layers of sediment deep below the ice sheet, pulling up the core in lengths up to 3 m long, the researchers examined the sediment for tell-tale indications of the environmental conditions under which it was deposited. They encountered a wide variety of sediment types from fine-grained muds through to firmer gravels with larger rocks embedded within.

“We saw a lot of variability. Some of the sediment was typical of deposits that occur under an ice sheet like we have at Crary Ice Rise today. But we also saw material that’s more typical of an open ocean, an ice shelf floating over ocean, or an ice-shelf margin with icebergs calving off,” says Co-Chief Scientist Dr Molly Patterson (Binghamton University, United States).

Open ocean conditions were indicated by the presence of shell fragments and the remains of marine organisms that require light to survive, implying the lack of ice above. Although it is already thought that there has been open ocean in this region in the past, indicating partial or total retreat of the Ross Ice Shelf, and potential collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, there is uncertainty about which time periods this occurred in.

“This new record provides sequences of environmental conditions through time, and ground truths the presence of open ocean in this region. In addition to pinning down the time when this occurred and the corresponding global temperature, analysis will help us quantify the environmental factors that drove the ice sheet retreat, such as determining what the ocean temperatures were at that time,” says Patterson.

Formidable logistical and technical challenges overcome on third attempt

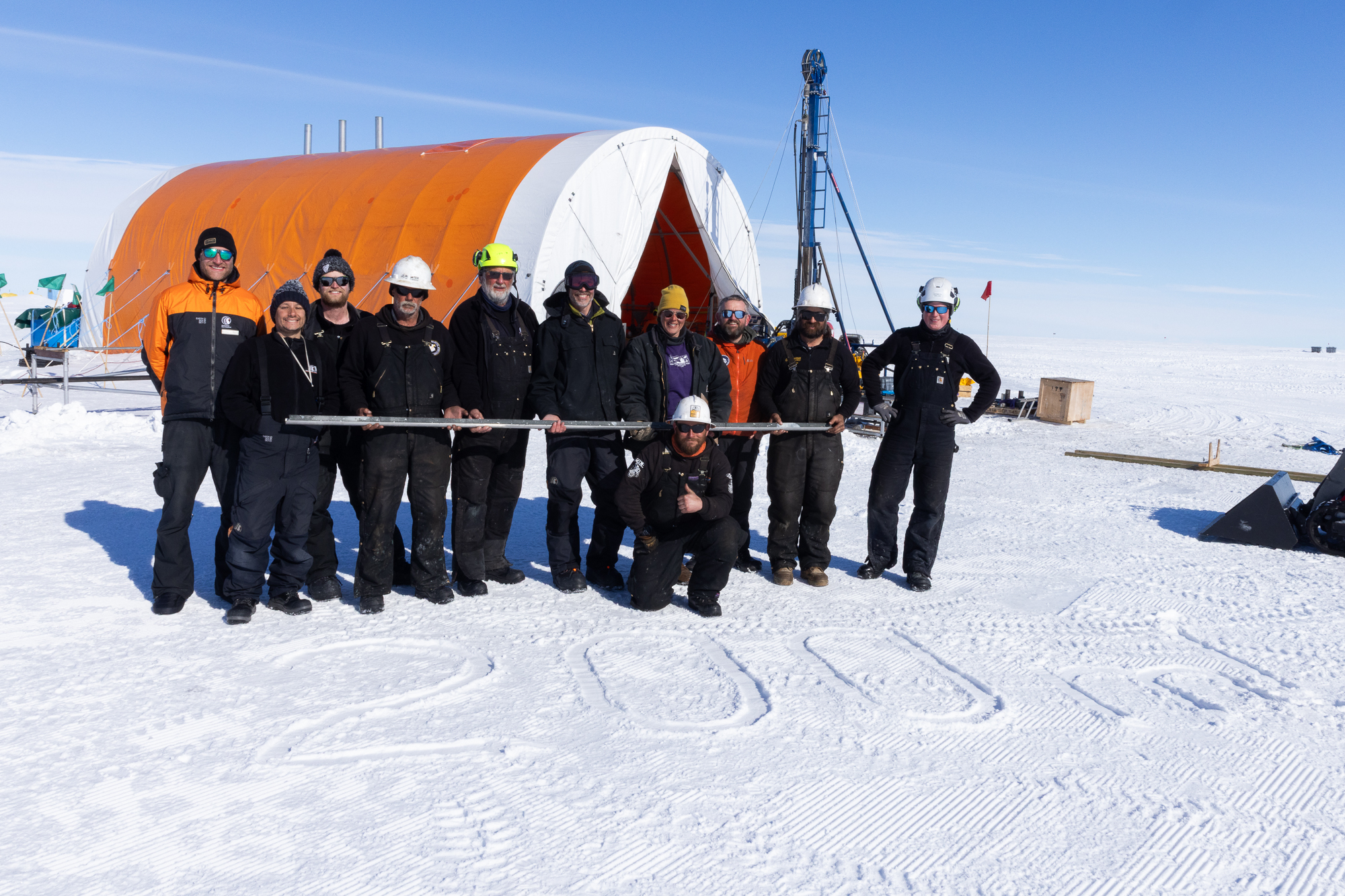

The team of 29 scientists, drillers, engineers and polar specialists living in tents on the snow at Crary Ice Rise knew that success was not guaranteed – SWAIS2C’s previous two attempts at drilling had been thwarted by technical challenges. This was not unexpected – no-one has ever drilled geological records this deep under an ice sheet and so far away from any main base of resources.

“To our knowledge, the longest sediment cores previously drilled under an ice sheet are less than 10 m. We exceeded our target of 200 m, and undertook this 700 km from the nearest base – this is Antarctic frontier science,” says Dr Patterson.

This groundbreaking work was supported by logistical contributions from two national Antarctic programs. Antarctica New Zealand provided the traverse capability to tow the custom-designed drilling system and field supplies 1100km across the Ross Ice Shelf. This team then established and operated the remote field camp through a nearly 10-week season. The National Science Foundation’s United States Antarctic Program also provided critical airlift and other logistical support. Weather presented a significant challenge, with the drillers’ and scientists’ flights into camp delayed by weeks due to freezing fog at the site.

To access the elusive sediment, the team had to first use a hot-water drill to melt a hole through 523 m of ice, then lowered more than 1300 m of ‘riser’ and ‘drill string’ pipe down the hole. Once the core was pulled up, the scientists described, photographed and x-rayed the tubes of sediment, and took samples. The team worked in shifts around the clock to make the best use of limited time on site.

“It was a great feeling when that first core came up, but then you start worrying about the next core and the next core after that. So, it's stressful right up until the end. But we’re thrilled to have learnt from our previous challenges and to have successfully retrieved this geological record that will help the world prepare for the impacts of climate change,” says Dr Horgan.

The core has been transported back to Scott Base and will soon make its way to New Zealand. Samples will then be sent to SWAIS2C scientists around the world for further analysis.

“Our multi-disciplinary international team is already collaborating to unravel the climate secrets hidden in the core. With our drilling system having been put to the test under these tough Antarctic conditions and passing with flying colours, we’re looking ahead to plan future drilling to continue our mission to learn more about the sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to global warming,” says Dr Horgan.

- The SWAIS2C Project Manager is Earth Sciences New Zealand, and the Drilling Services Manager is Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington. Logistical support comes from Antarctica New Zealand (K862A-2324, K862A-2425, K862A-2526, K862B-2324, K862B-2425, K862B-2526) in collaboration with the United States Antarctic Program. Drilling is partly funded and supported by the ICDP. Significant additional funding and in-kind contributions have been provided by the Natural Environment Research Council, Alfred-Wegener-Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, National Science Foundation (NSF-2035029, 2034719, 2034883, 2034990, 2035035, and 2035138), German Research Foundation (grants KU 4292/1-1, MU 3670/3-1, KL 3314/4-1), Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Korea Polar Research Institute, National Institute of Polar Research, Antarctic Science Platform (ANTA1801), LIAG Institute for Applied Geophysics, AuScope, and the Australian and New Zealand IODP Consortium. This project is the first in Antarctica for the International Continental Scientific Drilling Project (ICDP), and follows on from other successful international Antarctic research programmes such as ANDRILL.

- More than 120 scientists from around 50 international research organisations are collaborating on the SWAIS2C project. SWAIS2C brings together researchers from New Zealand, the United States, Germany, Australia, Italy, Japan, Spain, Republic of Korea, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

- The SWAIS2C team drilled 228 m into the bedrock below 523m of ice, and recovered 218m of sediment.

- Approximately 680 million people live near coasts exposed to hazards caused by sea-level rise. 30 cm of sea-level rise is unavoidable by 2100 but the increase may be as much as 1-2 m if we follow a high-emissions pathway.

- SWAIS2C’s first field season took place in the Antarctic summer of 2023/24 at KIS3 (Kamb Ice Stream), our second season took place at KIS3 in 2024/25. At this season’s site Crary Ice Rise (CIR) the ice sits directly on the bedrock, while at KIS3 there is a 55-metre ocean cavity below the ice shelf.

- An animation showing the drilling process at CIR is available here.

- SWAIS2C’s 2024/25 season at KIS3 is documented in this 15-minute video.

- For more information about SWAIS2C visit www.swais2c.aq

This media release was prepared by the SWAIS2C project and distributed by Earth Sciences New Zealand, Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington and Antarctica New Zealand.